Based on the utility model registration of a Japanese company in China, we filed an injunction request with the administrative agency of a certain local city in China. This case study explains two solutions to overcoming local patent protectionism in China.

In the case of overcoming this deep-rooted situation in China, there are two solution routes to consider when IP infringement cases occur. Namely, there is a track for filing a lawsuit with the court to demand an injunction and compensation for damages, and the “administrative procedure” track for filing an application for an injunction with an administrative agency.

The client of this case is an SME that manufactures daily necessities and sells them in Japan and China. The client holds a utility model registration for the product in China, but discovered that copies of the client’s product are being sold in that country. We received a request to “remove the infringing goods from China.”

Whether or not the Chinese company’s counterfeit products infringed the client’s utility model rights was a delicate matter, but after discussing with an associated Chinese patent attorney, we selected “administrative procedures” as it was possible to settle the matter quickly through “administrative procedures.” We filed a request for an injunction, demanding the elimination of infringement, with a local administrative supervision bureau in Guangdong Province.

The infringing company was located in Guangdong Province, and in addition to actually selling counterfeit products on the real market, they also widely sold products using the Chinese E-commerce site “Tao Bao”.

However, the allegedly infringing product was not a complete copy of the utility model registration, and cleverly circumvented the client’s utility model right. Therefore, after discussion with our affiliated Chinese patent attorney, we asserted the legal theory of “indirect infringement” when filing the injunction request.

In addition, since it is very important to submit evidence of infringing goods in such “administrative procedures” in China, we tried to obtain them. However, since time had passed since the infringing goods appeared we were initially unable to obtain them. While it took a lot of time and effort to obtain the infringing goods, we finally managed to obtain them and submitted them to the Administrative Supervision Bureau as evidence.

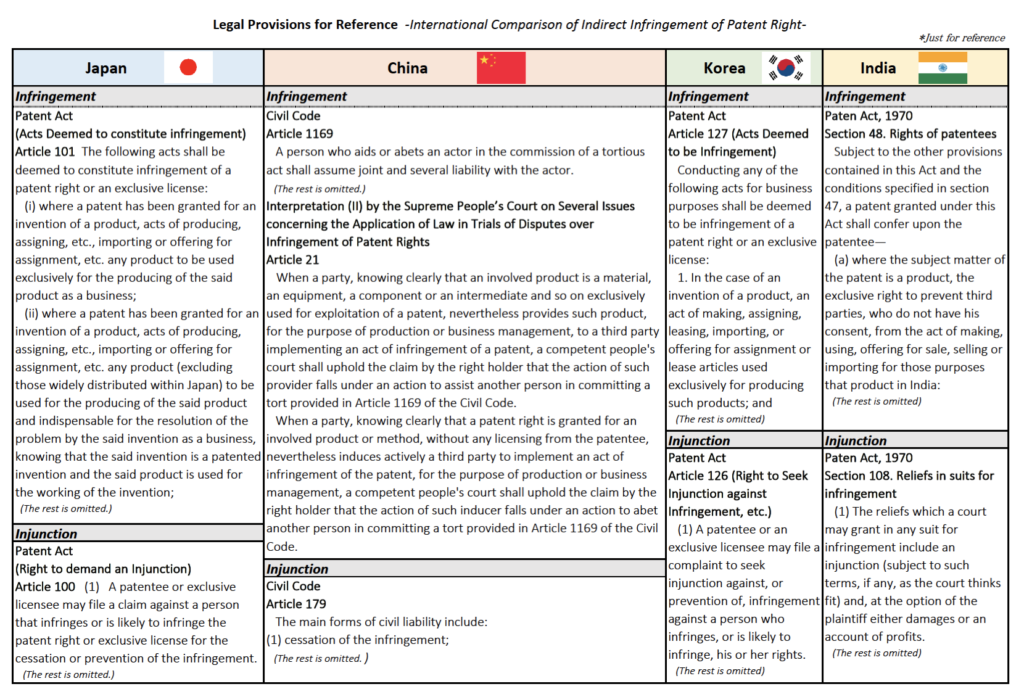

The doctrine of indirect infringement exists not only in China, but also in Japan, the United States, and Europe. Article 101 of patent law in Japan, Article 271 in the United States, Article 26 of the “Community Patent Convention” in Europe. In China, there is no provision in the Patent law, but was recognized by judicial interpretation.

The response of the Administrative Supervisory Bureau itself was user-friendly, and it was basically favorable for us. In “administrative procedures”, the officers in charge actually visited the manufacturing factory of the infringer and interrogated the person in charge of the factory to verify the infringing goods, confirm the inventory, and confirm the delivery destination.

As a result, the evidence of infringement was almost discovered, and it seemed to us that the case was going to be settled shortly with a favorable result for us.

Surprising Turn Of Events.

Just before the final administrative decision was made, the Administrative Supervision Office suddenly called the Chinese patent attorney and said, “In this case, we cannot make the decision of infringement. This trial was concluded.” The attitude of the board was so different from what had happened up until then, naturally, the Chinese patent attorney was very surprised to hear that, and asked for the reason. The member of the board simply said, “It’s already decided.”

Needless to say, I had a very bad feeling when I received this report from the Chinese patent attorney. It made me imagine that the infringer provided some kind of economic benefit to the board of Administrative Supervision Office. We had the same kind of experience in China before on another case in Beijing 20 years ago.

We had information that the infringing company was a well-known local company and a model company that was making effective use of intellectual property. In fact, in the Administrative Supervision Bureau’s decision, they dismissed our claim.

Also, it turned out that the infringer filed a request for an invalidation trial against our client’s utility model registration in the Patent Office. Regarding the decision, we were able to file a law suit with the higher people’s court of Guangdong, but it would have incurred high costs and been very time consuming.

New Solutions

Under these circumstances, I considered the matter seriously, examined various possibilities and came up with the following solutions.

We formally filed a lawsuit against the administrative decision with the Guangdong Higher People’s Court. This was just a “dummy lawsuit” – in other words, just only a written complaint would be submitted, and a substantive statement of reasons would not be submitted. The simple fact of a lawsuit itself would be established.

On the premise of this, we decided to conduct settlement negotiations with the infringer based on the following conditions.

The Chinese patent attorney strongly opposed this proposal. The reason is that “It is very dangerous to negotiate with an infringer whose background was unknown. We are unable to expect what kind of conditions might result, or what actions they might take.” After long discussions, finally, the client agreed to the following scenario which I proposed.

- We withdraw the lawsuit against the decision from the Administrative Bureau, on the basis that the infringer withdraw their lawsuit for invalidation against our utility model registration.

2. We have effective evidence to invalidate an infringer’s utility model registration, but we will not file an invalidation trial. In return, the infringer will no longer manufacture and sell infringing goods.

I ordered the Chinese patent attorney to propose a settlement to the infringer subject to the above conditions: this worked out well, and the case was finally settled. Three years have passed so far without incident.

Infringement cases involving foreign companies as plaintiffs in China are still disadvantageous to foreign companies. In particular, if SMEs (small and medium-sized enterprises) with limited funds attempt this action, especially in rural districts of China rather than in Beijing, Shanghai, etc., they will run into the wall of China’s regional protectionism.

As you see from the above, there is still the possibility that the eventual conclusions of such cases will be affected by the provision of bribes to administrative agencies and the court.

However, even under such circumstances, it is possible to eliminate infringing goods by devising creative measures, if you try.

Some Related Materials:

A link to an English translation of Japanese Patent law. You can search on Article 101.

Here is a graphic depicting an international comparison of indirect infringement rights.

A key point in resolving disputes in China is to keep in mind that “any situation can arise that we would not normally experience in our own country.” Understanding, for example, the two solutions to overcoming local patent protectionism in China brings home the importance of such a perspective.

At Kimura & Partners, we focus on supporting domestic and foreign companies, especially SMEs, register and defend their IP in what we call the IP battleground. As to this article… it’s important to understand the concept of “Secret Prior Art” and its different treatment in the PTOs of different countries.